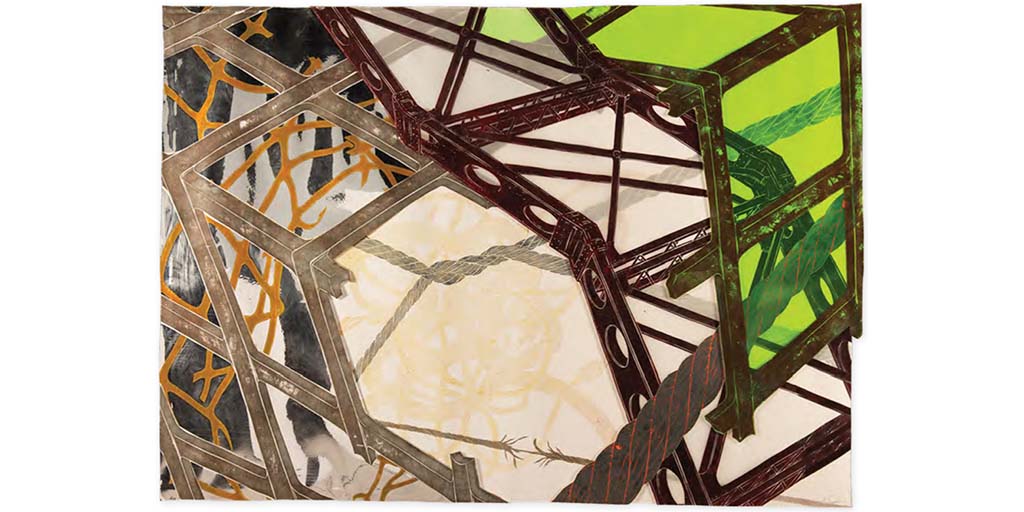

A group of students gathers around an artwork on a wall in the “Currents” exhibit at the IU Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, a woodcut and mixed media collage by Nicola López, a contemporary American artist. The piece, titled “Structural Detour 20: Bridge and Square Fences Embrace around the Knot and Rope” (2011) is an abstract work depicting fragments of bridges and fences, steel structures and cables, as well as a more pliable, natural-looking rope and a weblike netting. Through the spaces outlined by these structures is a rope worn down to a single thread and the faint image of a knotted rope behind it.

PBS Professor Aina Puce’s course, “Art and the Brain,” ignites conversations between two disciplines.

Bridges, fences? A near-broken connection, a densely knotted rope? What does it mean? Ideas are bouncing furiously back and forth between the students, each one building on, connecting to, or modifying the others. Before you know it, 45 minutes have passed, but the ideas continue to flow, setting the stage for part two of today’s class, a visit to the museum’s art-making studio and an exercise in which each student recreates and deconstructs a familiar place, using materials from the studio.

Convergences

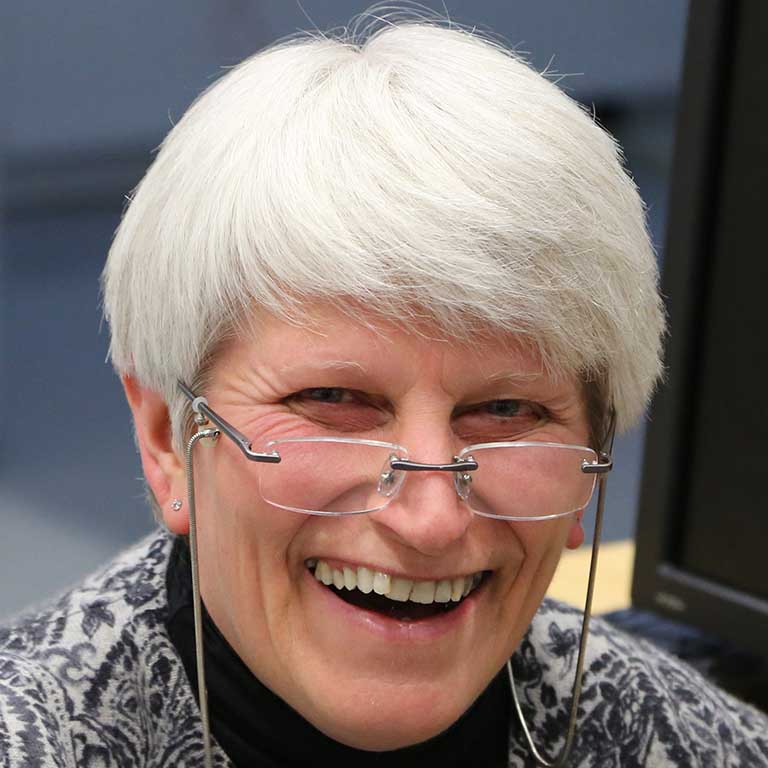

Welcome to PBS Professor Aina Puce’s “Art and the Brain,” a class that typically meets in the spacious Itter Objects Study Room on the museum’s third floor. A self-described “art enthusiast and brain nerd,” Puce has worked in the neuroscience field for 40 years and for 30 of those years as a photographer who has exhibited and sold her work. More recently, she has also begun to lead guided tours as a docent at the art museum, so is immersed in knowledge about its holdings and makes special use of the collection throughout the semester.

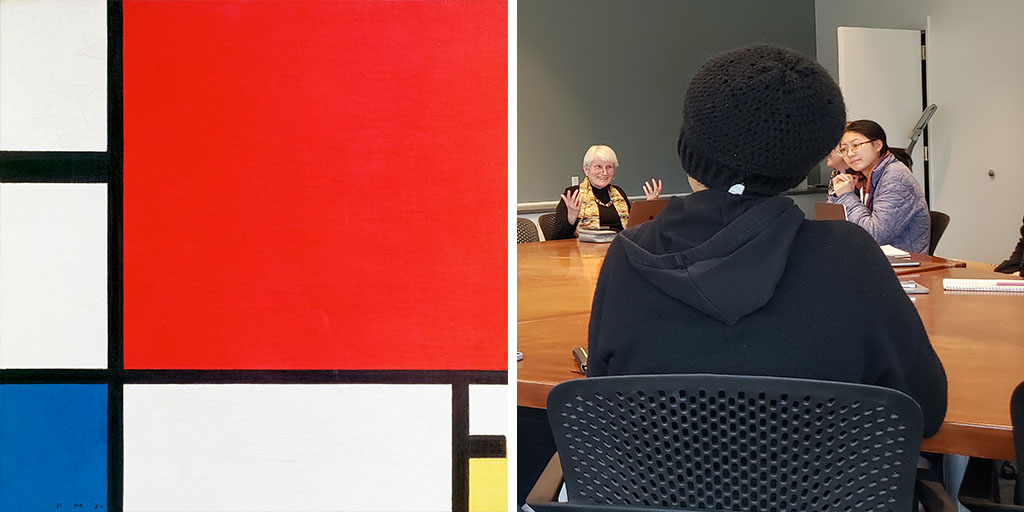

Today in the second-floor gallery, the class is led by museum art therapist Lauren Daugherty and several museum interns, who jointly jumpstarted the discussion which has taken off like wildfire. Together they are demonstrating a version of a museum-based learning and art experience, which combines discussion of the artwork with a guided art-making exercise. As the only U.S. university art museum with a licensed art therapist on staff, IU is a trailblazer in this respect. As Daugherty explains in a lecture in a subsequent class, the activity of viewing and making art engages the mind and brain on numerous levels – kinesthetic, sensory, visual, affective, and cognitive, thereby generating rich material for self-reflection, evaluation, and art therapy.

Today’s class, however, reflects only one strand of the multifaceted knot which Puce teases apart in the course of the semester, enabling the links between the two disciplines to emerge without imposing a particular framework on how the convergences should or could occur. As a result, these convergences proliferate in numerous, sometimes unexpected, always awe-inspiring ways.

Through faculty lectures and student discussions, “Art and the Brain” considers a cross-section of topics: the brain’s visual and motor systems on which making and viewing art depend, the shared preoccupations of both neuroscientists and artists with the perception of faces and bodies, motion and emotion, as well as the impact of mental and physical disabilities on artists and their work. Puce considers a variety of artistic movements and forms of visual media, from painting, print and drawing to ceramics, sculpture and photography. In a final group project, students develop an understanding and interpretation of one of the museum’s artworks through the dual lens of brain science and art. Along the way we hear from neuroscientists either studying or (like Puce) practicing art, another Bloomington photographer, Chaz Mottinger, and museum staff members Daugherty and Director David Brenneman, who illuminates some of the challenges that the museum, and others like it, have wrestled with in recent years.

A tangled knot

Though too numerous to list in full, here are a few of the strands of insight that surface from this tangled knot whereby art and neuroscience intersect.

Puce, for example, explores the shared interest in detailed, anatomical study of how faces and bodies move and express emotion, using photography and its offshoots as a tool to capture motion and emotion in anatomical forms. Zooming in on the brain’s visual system, Puce describes the brain’s mechanisms for turning a three-dimensional world into a flat image. “Nature,” Puce says, “has given us four secret weapons at our disposal: shading, relative sizes of objects, occlusion, and stereopsis (the effect of having two eyes), which allow us to see depth and distance from two flat retinal images. And these “tricks we use to convince our brains and cells that there’s a three-dimensional world,” she suggests, are the very techniques artists have used for centuries to create convincing two-dimensional realist images from a three-dimensional world.

Nature has given us four secret weapons at our disposal: shading, relative sizes of objects, occlusion, and stereopsis.

– Aina Puce

Beyond realist images, abstract artists have also uncovered principles of the biological visual system. According to Italian neuroscientist Luca Ticini, a Zoom visitor to the class, artists “explored the brain before neuroscientists had the technology.” Modernist Kazimir Malevich’s painting of a red square, for example – his attempt to represent “the essential building blocks of form” – is, for scientists many years later, an example of a stimulus that best enables the brain to perceive color. Likewise, 20th-century Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s straight black lines and rectangles in primary color paintings are the culmination of his long exploration into what he similarly considered “the building blocks of all forms.” Thirty years later, neurophysiologists discovered that the building blocks for perception of form are straight lines. “Artists,” says Ticini, “discovered before the physiologists that there are cells that respond to straight lines.”

Another Zoom visitor to the class, Finnish Professor Emerita of neuroscience Riitta Hari (now teaching in an art department) further explores how the two disciplines “speak to each other.” As Hari explains, from the perspective of neuroscience, we each construct “caricature worlds, bringing together a set of sensory input alongside our unique prior experiences, and our bodily and emotional states.” Our perceptions are a kind of inference, she says, “a best guess based on both sensory input and what we bring to it.” Likewise, as some art theorists suggest, no artwork is complete without a viewer’s sensory and emotional participation, which includes the collection of associations and memories we draw on to make sense of any artwork. In this sense, looking at art is a reenactment of the visual/perceptual system writ large.

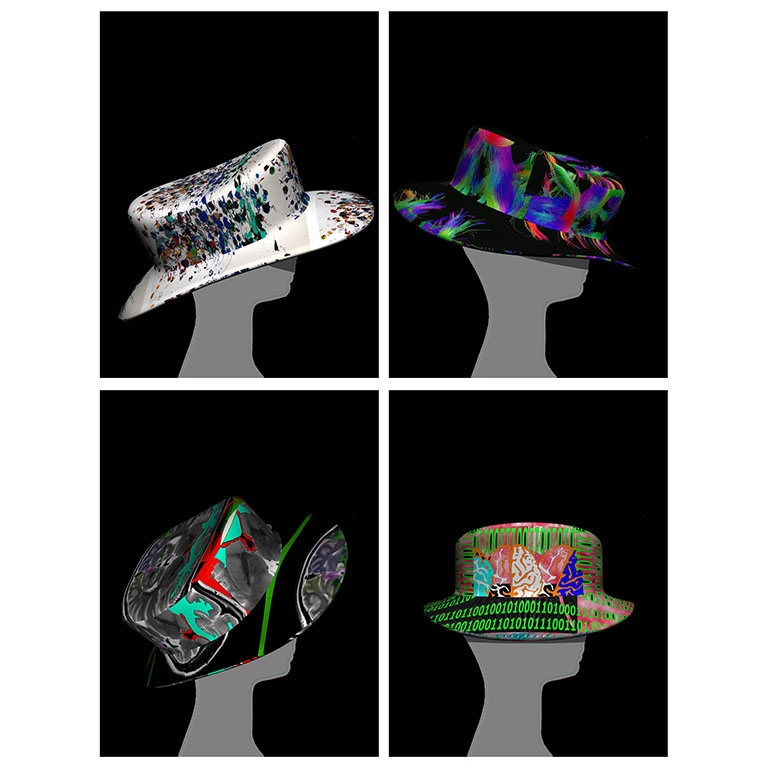

Puce has spent a career in social and cognitive neuroscience, studying how different parts of the brain respond to different kinds of content, whether portraits or landscapes, bodies or objects, scenes that depict social relationships and varying emotion, and those that show motion and action. Using this knowledge, neuroscientists are now drawing on current technology – neuroimaging, eye-trackers, and portable EEG systems to explore the cognitive and affective experiences of art and museum design.

Each class brings new twists and turns in the conversation: a look, for example, at such extraordinary artists as Vincent Van Gogh, Amedeo Modigliani, Frida Kahlo, Willem de Kooning, and Chuck Close to explore how physical and mental disability can affect an artist’s work or the art-making experience.

The students in the class also play a key role in shaping the direction of the course. Two EMA docents and its public experiences manager audited the class. The mixed-level students include a formally trained artist/PBS lab manager planning for grad school in psychology and art, and some truly remarkable seniors and graduate students from PBS and other departments and schools.

Each class unravels new threads that both add to the complexity and illuminate the knotty conjunctions of art and neuroscience. Bridges and fences. Near broken connections and a knotted rope. Indeed.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts