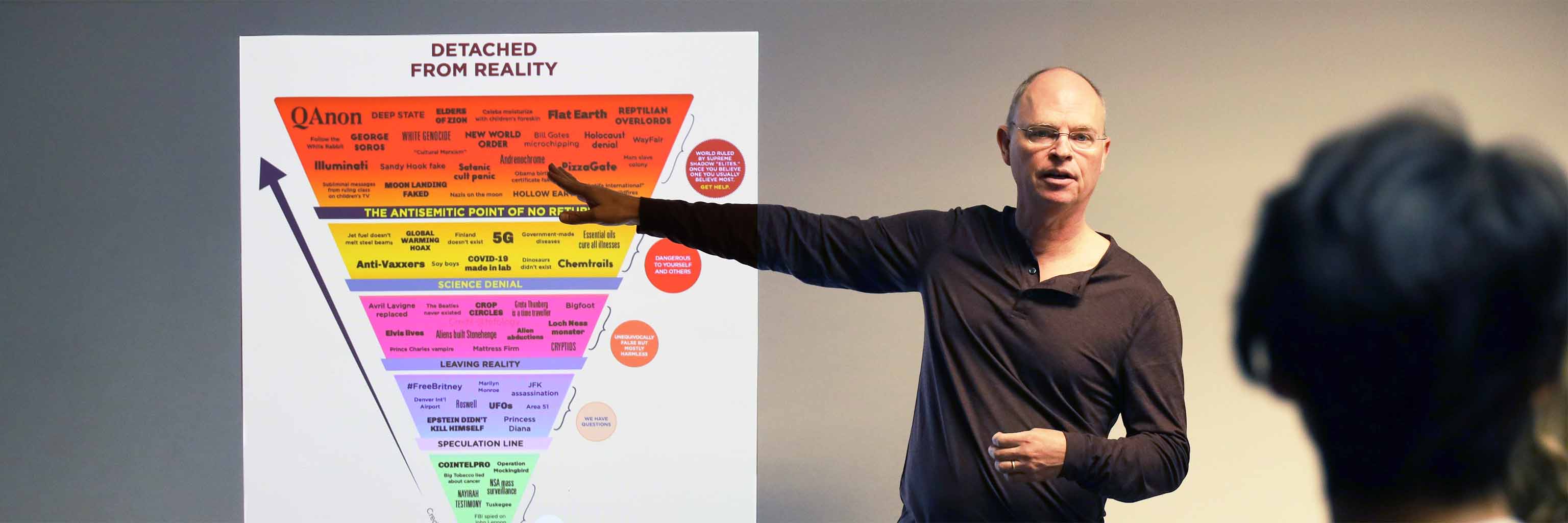

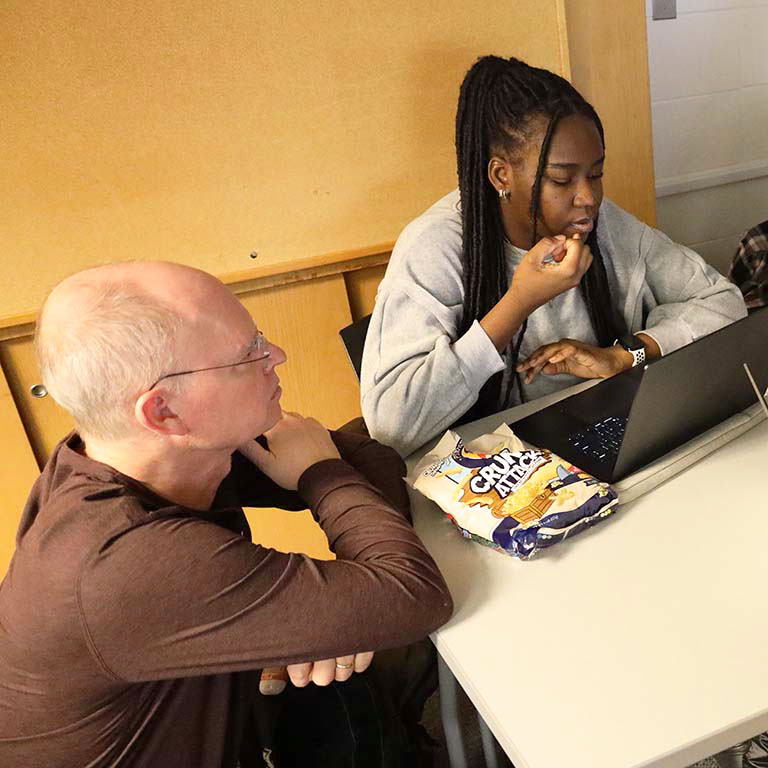

Conspiracy theories abound, and whether or not we buy into them, it’s hard not to admit at least a little fascination, and sometimes even more than a little shock, revulsion or horror at the turns they can take. All of which makes them a tantalizing test case for PBS Professor Tom Busey’s PSY-X 150, The Psychology of Pseudoscience and Conspiracy Theories, in which students learn to use the tools and techniques with which psychologists study human behavior.

“It’s a course that focuses on conspiracy theories but is really just about measuring human behavior,” Busey explains. “Conspiracy theory believers are just one example of people who have unusual or atypical beliefs, and they have behaviors and personality characteristics in common. But their motivations and characteristics are not all that different than other people, and so the things we learn apply to the rest of human behavior.”

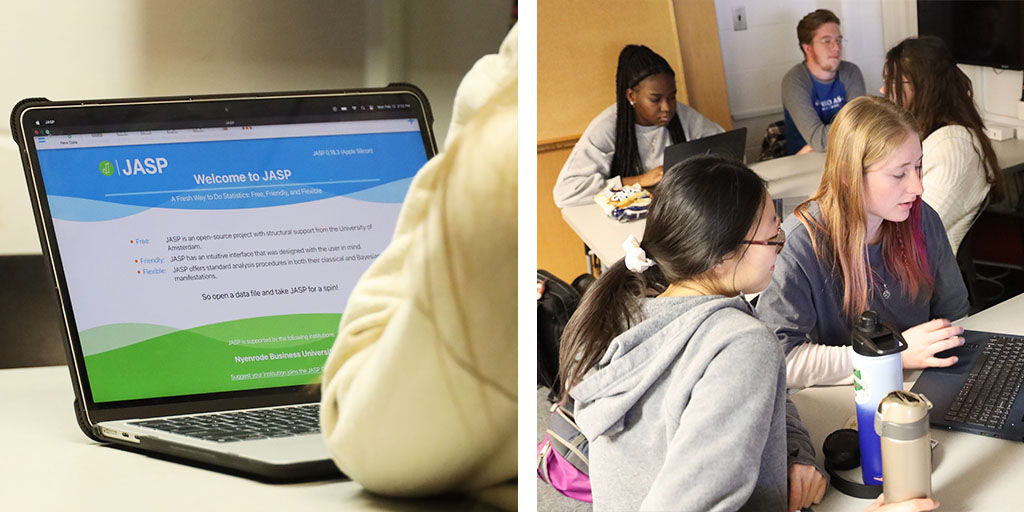

As such the topic is an especially rich and abundant source of data for this ASURE course (an Arts and Sciences Undergraduate Research Experience), designed to teach students some basic skills of data collection and analysis.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts