Psychosis often begins not with characteristic disturbances of the mind – delusions like paranoia or hallucinations – but with disturbances in the way we move our body. For researchers like Indiana University Assistant Professor Alexandra Moussa-Tooks in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, these motor disturbances offer critical insights into the condition of psychosis itself.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, senior-author Moussa-Tooks and first-author Heather Burrell Ward, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, explore one such motor ability – grip strength – to uncover the mechanisms linking motor disturbances to psychosis.

As Moussa-Tooks explains: “Poor grip strength has been associated with many negative outcomes in a variety of people: lower well-being, higher risk of mortality, poor day-to-day functioning, poor quality of life. Grip strength seems to capture that things are not going well. But it hasn’t been well studied in relation to brain function or early psychosis. Our study looks at how grip strength may be an important sign of brain and psychological health in early psychosis.”

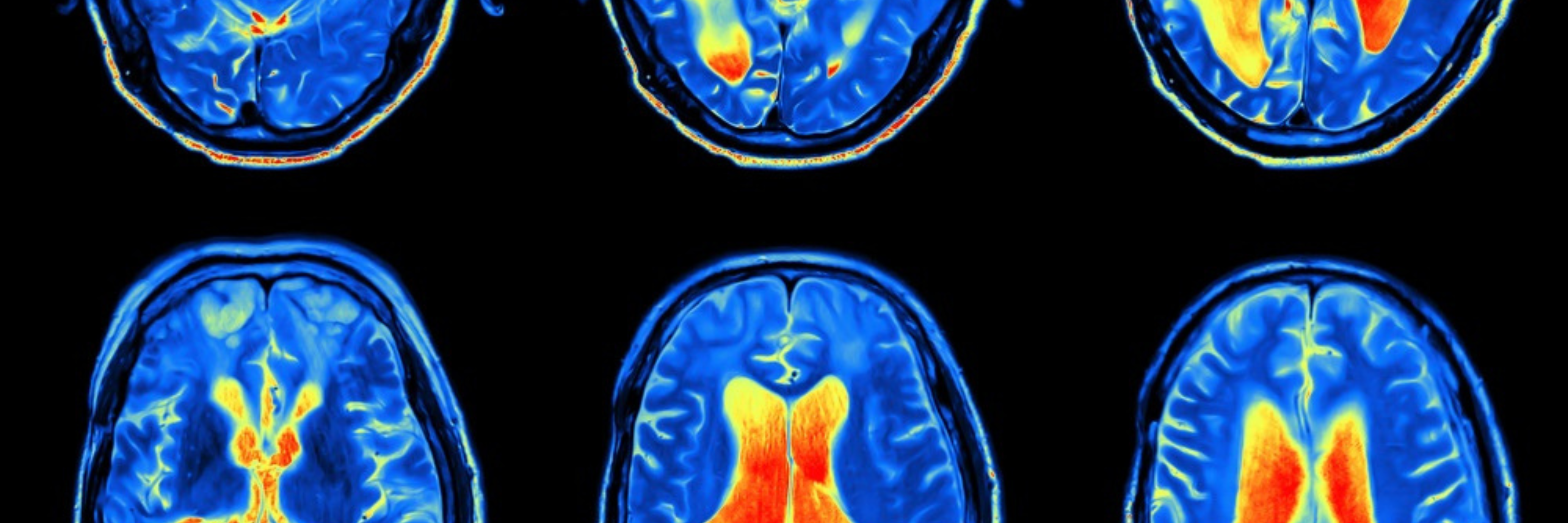

The study is the first to suggest that grip strength and overall well-being share common patterns of brain connectivity. It shows that impairment in grip strength and well-being may reflect alterations in what researchers call “resting-state functional connectivity,” a measure of brain network function that may be key to understanding psychosis.

Through a novel neuroimaging analysis, Moussa-Tooks and her collaborators demonstrate that brain networks with important roles in both motor and cognitive function play key roles in gripping ability and mental well-being. Their findings lay the groundwork for interventions aimed at improving functioning and wellness in early psychosis.

A unifying brain circuit explanation

The study’s data came from the Human Connectome Project for Early Psychosis, a large initiative conducted from 2016 to 2020 across multiple sites, among them the IU School of Medicine. It included 89 individuals in the first five years of psychotic illness and 51 healthy controls for whom age- or medication-related motor decline could be ruled out.

The analysis confirmed that participants with early psychosis had lower grip strength and well-being scores than healthy controls. These metrics related to three key brain regions —the anterior cingulate cortex, sensorimotor cortex, and cerebellum— each of which were shown to be connected to the default mode network. Higher grip strength and greater well-being correlated with greater connectivity between these regions and the default mode network.

Identifying brain targets for new treatments

“Our findings are particularly exciting because they identify potential brain targets for new treatments for psychosis,” Ward said. For example, both researchers see enormous potential in transcranial magnetic stimulation. If in psychosis there is poor communication within the default mode network, TMS is a non-invasive tool that can be used to directly increase that connectivity. Motor training, like exercise, to strengthen brain networks indirectly can offer another promising strategy.

“Grip strength and other motor functions,” Moussa-Tooks explains, “are easily assessed and more readily interpretable than complex tasks often used to study psychosis. Our work is showing that these seemingly simple metrics can help us understanding disturbances not only in the motor system, but across complex brain systems that give rise to the complex symptoms we see in psychosis.”

Consider the following analogy, she suggests: “If psychosis is a house on fire, symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations are the smoke. In a fire you don’t target the smoke, you target the fire and its source. And yet, currently that’s not how we approach treatment for psychosis. Motor disturbances help us get closer to identifying where the fire may have started and spread. They are more fundamental in the sense that they’re easier to link to different disturbances in the brain.”

With this new study researchers are getting closer to the fire. By drawing a line between motor function and mental health – from grip strength and well-being to patterns of brain connectivity with a key role in psychosis – they are mapping out new paths for understanding and treating an elusive disorder.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts